Economic, Tourist, And Cultural Development Join Human Collateral Damage Of State-Backed Economic Terror Campaign

“The city was thriving,” said Ramsey Short, the British editor in chief of Time Out Beirut, a four-month-old publication that had become an indispensable tool to navigate Beirut’s busy cultural and entertainment scene.

The July issue, with its cover story on Lebanon’s summer festivals and its 114 pages, has become a memento of a time that never happened: all the events and shows have been canceled. The next issue has been postponed until further notice.

“Just like that, it’s all gone,” Mr. Short said. “And I don’t think we’ll return to that world any time soon.”

The war caught most people by surprise. Dozens of festivals, concerts and shows have been canceled, including elaborate months-long programs in Baalbeck; in Beiteddine, south of the capital, where open-air concerts are held in a 19th-century palace in the Chouf mountains; and in Byblos, a coastal town north of Beirut. Ticketholders are being reimbursed. Organizers of Liban Jazz, scheduled for September, are trying to keep that festival alive, perhaps as a charity event in Paris. Along the bombed-out coastal highway in the south between Beirut and Tyre, dozens of fancy resorts are deserted, their once-pristine beaches polluted by an oil slick.

The Baalbeck International Festival, set inside stunning Roman ruins in the middle of the Bekaa Valley, east of Beirut, was to celebrate its 50th anniversary this year. Organizers had scheduled performances by Lebanon’s national diva, Fairuz; the Ballet Theater of St. Petersburg; and the Budapest Symphony Orchestra and Opera of Nice in a joint production of Donizetti’s “Lucia di Lammermoor.”

Thousands of well-to-do Beirutis had bought tickets and were prepared to drive two hours to attend these open-air productions between the temples of Jupiter and Bacchus. Instead, in the town of Baalbeck itself, away from the historic ruins, Israeli Air Force planes have leveled dozens of buildings in recent days. Baalbeck is a stronghold of the militant Shiite group Hezbollah; the Israeli military campaign in Lebanon began after a Hezbollah raid into Israel on July 12.

“I feel stupid because I was so optimistic,” said Carole Ammoun, a 27-year-old actress who had been performing in a local version of Eve Ensler’s “Vagina Monologues,” called here “Hakeh Nesswan,” or “Women’s Talk.” The play, which was originally scheduled for five nights, had been extended for three months straight.

“It was such a compliment to perform in something that was successful and that people enjoyed,” said Ms. Ammoun, a bubbly woman with a large flashing smile. “We broke so many taboos talking about sexuality in an Arab country. There was a real sense that we were opening new doors.” ...

Some artists have channeled similar feelings into their work. Mazen Kerbaj recorded a musical piece with his trumpet and the sound of bombs falling on Beirut in the background for a duet he called “Starry Night.” ...

In Hamra, Beirut’s faded former commercial district, Hania Mroué had been looking forward to July as she opened the Metropolis, a theater for art-house movies. For the premiere, attended by the culture minister and the French ambassador, she picked “Les Amitiés Maléfiques” (“Poison Friends”) by the French director Emmanuel Bourdieu, which won the Critics’ Week Grand Prix in Cannes. The next day the war began.

Now about 40 people from Beirut’s bombed-out southern suburbs sleep in her movie theater and offices, which are two floors underground. During the day she shows films and documentaries to keep the children busy.

Last Monday she decided to reopen the theater to the public for daily screenings at 6 p.m.: early enough, she said with grim Lebanese humor, so the audience can go home before the bombing begins.

“It’s important to be able to talk about other things than Israel and Hezbollah,” said Ms. Mroué, 31, whose soft features belie her steeliness. “We will have all the time to analyze, to argue and even to cry about all this later. This is why theaters like this are important: so that you can live, even during a war.”

Last week she asked two doctors from the nearby American University of Beirut hospital to vaccinate the children in the theater. At the same time she somehow managed to obtain a Sri Lankan movie — “The Forsaken Land” — that had been stuck in Damascus for three weeks. Next she plans to show movies by the late Lebanese filmmaker Maroun Baghdadi about the country’s civil war.

“It so hurts my heart to admit this that words fail me,” she said. “We had such a promising year. I don’t think we’ve realized what we have just lost.” ...

As everywhere, the war dominates discussions. Many talk about feelings of loss, abandonment or despair. What seems to rankle most, though, is the sense that a huge collective bubble has been pricked without warning.

“It took a long time to get to where we were,” said Mr. Abdel Baki, the musician, as the sun slowly dropped into the sea. “Things won’t be the same anymore. It’s the uncertainty that’s unsettling. It shows how precarious our lives were.”

Jad Mouawad "In Beirut, Cultural Life Is Another War Casualty" New York Times, July 31, 2006

http://www.nytimes.com/2006/07/31/arts/31cult.html?hp&ex=1154404800&en=cbfb3dd947d69568&ei=5094&partner

=homepage

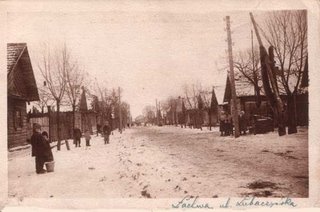

The ruins of the Greek temple at Tyre, Lebanon. Situated on the coast, this site has been important since Phoenician times. Alexander the Great passed this way. But the area has been prone to devastation, not only caused by earthquakes local to Lebanon but also by tsunamis. These can be triggered by submarine slides on the Levant continental margin or by other geological events (earthquakes, eruptions) elsewhere in the eastern Mediterranean.

Photo and caption credit: © 2000 Rob Butler, The Dead Sea Transform in Lebanon, School of Earth Sciences, Leeds University, United Kingdom. With thanks.